This month in Ontario, lawyers and paralegals will vote for the next set of “Benchers” at the Law Society of Ontario (LSO). For those unfamiliar with the term, Benchers are the board of directors at the LSO, the regulatory body that governs lawyers and paralegals in Ontario. Bencher terms are for four years. Eligible voters can vote for up to 20 lawyers in the Toronto region and 20 lawyers outside of Toronto. There is a common misconception that Benchers represent lawyers, much like a member of parliament represents their constituents. Benchers actually represent the interests of the public and regulate the profession. Still confused? Precedent Magazine published a helpful article: What do Benchers at the Law Society of Ontario Actually Do? For this election my Twitter and LinkedIn feeds are filled with #BencherElection2019 posts, conversations, podcasts, endorsements, etc. Looking at this level of engagement, one might think that every lawyer in Ontario is super keen to vote and discuss the pressing issues facing our profession. Unfortunately, this is likely far from the truth. Social media platforms, and especially Twitter, can be massive echo chambers. While lawyers on social media appear to be engaged in the election, the historical data on voter turnout suggests that the majority of lawyers are really apathetic. Large Firm Lawyers Vote (Sole Practitioners, Not So Much) The LSO published a comprehensive report on voter turnout, covering election results from 1987 to 2015. Generally, turnout has decreased with every election. 10,287 of the 18,369 eligible voters (or 56%) voted in the 1987 election. Fast forward to 2015. Despite the technological advancement of online voting and a relatively robust #BencherElection engagement on Twitter, 2015 had the lowest percentage of voter turnout in the years documented. Of the 47,396 eligible voters (notice the significant increase in the number of lawyers in Ontario) only 16,040 (or 33.84%) voted. Interestingly, in private practice, the voting-lawyers are from firms of between 76-100 lawyers (over 77% voted in the last election) and firms of over 100 lawyers (over 50% voted). Could this be due to the constant pressure from management to vote for the lawyers who are running from those firms? Hmm. Sole practitioners, who make up the largest category of lawyers in private practice, had the lowest voter turnout for private practice lawyers with only 36.35%. In 2015, only 24.55% of the over 23,000 lawyers not in private practice (lawyers employed in government, corporations, academia) voted. Also, consistently every year, a slightly higher percentage of lawyers who identify as male vote than lawyers who identify as female. In the last election 35.66% of all male lawyers voted, while only 31.23% of female lawyers voted. Why You Should Vote (and Encourage Others to as Well) These statistics tell me that most lawyers do not prioritize the Bencher election. Understandably, many lawyers would prefer to spend time on other aspects of their lives rather than taking the time to research the issues, research the candidates, sit down at a computer, and vote. The problem is that there are several important issues that the LSO (and the newly elected Benchers) will be grappling with, and these issues affect not only the legal profession as a whole, but you as an individual lawyer. I will not discuss the issues in detail here but a few examples: improving access to justice, ensuring lawyers are competent to practice and providing remedial or disciplinary measure for those who are not, the licensing process, entity-based regulation, diversity & inclusion initiatives, the cost of legal education, alternative business structures, etc. In the past, Benchers have made some important (and sometimes controversial) decisions: changing the name from Law Society of Upper Canada to Law Society of Ontario; introducing the Law Practice Program to assist with the articling crisis; deciding not to accredit Trinity Western University; implementing the Statement of Principles requirement; approving the recent public awareness campaign; etc. If you are interested, the minutes and transcripts from Convocation tell you how the incumbent Benchers who are running again voted on past issues (just click on the year on the left-hand side). As an example, these are the Minutes from December 1, 2017 which involved a vote on Mr. Groia’s “conscientious objector” motion regarding the Statement of Principles. All lawyers and paralegals should care about who will be making the decisions about each of these issues. Want to Vote and Don’t Have the Time to Research all those Lawyers? “What do you mean there are 128 lawyers running? I don’t have the time to research all of them!” I know many of you are thinking this and it is a valid observation. I have a few suggestions for you: First, several people and organizations want to make this easier for you and have compiled the information you need for the election in one place. For example, Colin Lachance has organized and published the website LSOBencher.com where the candidates can submit their profile and their positions on the current issues. The Ontario Bar Association has made a website profiling its members who are running. The Law Times also has a website listing the candidates. Sean Robichaud has a podcast featuring some of the candidates. Or you can follow #BencherElection2019 on Twitter. These are just some of the places you can go to get the information you need. Does that still sound like a lot of work? Another option is to seek out a lawyer you trust (and who has the time and interest to do the research) and ask for their recommendations (thanks, Morgan Sim for this suggestion). Or, there is my approach. I really dislike receiving emails and flyers from candidates. Not only do they fill my inbox and recycling container, I do not think it is fair to those candidates who cannot cover the expense for such advertising. Not all candidates can pay for the email list or can afford to have fliers printed and mailed out. For the last two Bencher elections I have made sure not to check off the box on our annual reports allowing Benchers to email me. Instead, I only look at one thing: The Voting Guide provided by the LSO. Each candidate gets one page and one page only to convince me why I should vote for them. I see it as a level playing field for all candidates. I’m not saying my approach is perfect, but as a rather busy person who wants to vote, this is the best use of my time. (Hint: the Voting Guide is searchable if there was a particular issue that interested you, for example, the Statement of Principles.) So, Vote! No excuses this year. Get out and vote. Encourage other lawyers to do the same. You will receive an email from the LSO in the second week of April with a link and explanation on how to vote. Keep an eye out for it and vote by April 30, 2019. Whatever approach you take, I just ask that you take a few minutes to vote and tell all the lawyers in your network to vote as well!

1 Comment

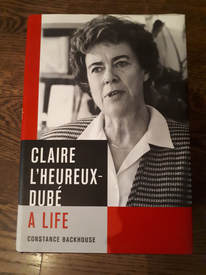

I am happy to unveil a new series I have started for 2019 focused on improving equality, diversity, and inclusion (EDI) in the legal profession (I don't have a witty title for this series yet, so all suggestions welcomed!) The idea for this series surfaced last year when I attended a women lawyers conference where the conversation quickly turned to criticizing and calling out law firms for not doing enough to make a positive change. The conversation went on for quite some time with example after example of all that is wrong with law firms. Unfortunately, no one talked about possible solutions. While I am not saying that this criticism was unwarranted, I do believe it is easier to sit back and critique than it is to be out there trying to make the changes that need to happen. . . And I know some firms are putting in some effort. So with my new series, I wanted to reach out to law firms and find out what they are doing to advance EDI in their firms. Are they doing anything? What is working? What isn't? What is the end-goal? How do they measure "success"? The posts will include a set of five questions that each firm will answer. My simple goal is to start a conversation, find out what is happening in this area in law firms across Canada, and perhaps we can all learn from each other. For my first post, I sat down with Lisa Munro, the Managing Partner of Lerners LLP to discuss the EDI initiatives at her firm: 1. ALMOST ALL LAW FIRMS HAVE AN EDI POLICY OR COMMITMENT ON THEIR WEBSITE. WHAT DOES EDI MEAN TO YOUR FIRM AND IS IMPROVING EDI A PRIORITY? Improving equality, diversity, and inclusion is definitely a priority for Lerners. A lot of firms, Lerners included, have historically been very lawyer-centric, the idea being that the lawyers are the economic drivers of the firm. While you can’t argue with this fact, focusing most efforts on the lawyers means that we are leaving behind the rest of the team. I think that one of the things that diversity and inclusion committees have done for law firms has been to put the focus on the culture of a firm and on all the people that play a part in serving our clients. We are now realizing that it can’t just be all about the lawyers and ensuring that the lawyers are happy and professionally fulfilled. So at Lerners we place a lot of emphasis on the inclusion part of EDI which means, do people feel like they are a part of the firm? Do they feel like they are valued for their contributions? Do they feel like their voices are heard? Do they feel that if they have concerns or complaints there is a place for them to go to address them? Do they feel that their colleagues listen to them? Do they have opportunities for professional advancement? All of those things go far beyond the equality and diversity issues that many of us are now talking about. I constituted our firm’s Diversity and Inclusion Committee in late 2017, and started with a survey. I think a lot of firms start there. As a result of the feedback we received from that survey, I placed as much emphasis on inclusion as I did on equality and diversity issues. We learned that some people felt isolated in the group. And so, our task was, what do we do to make people feel that they belong at this firm? A lot of the initiatives that we have tackled as a Committee have tried to draw people in and get them to participate, get to know one another, and work together. That part is very important for us. If we focus on equality and diversity, our history has been very much that Lerners is a place where women thrive and have voices and have opportunities for leadership. I am very proud of that. We’ve had that reputation for a very long time, mostly because of our two strong senior partners, one of whom is Janet Stewart, still with the firm. She was our managing partner in both offices for many years at a time when there were very few women managing firms. She was someone who had a practice and she was well respected. People listened to her. She had influence. Janet was also supported by our senior partner in Toronto, Earl Cherniak. He and Janet were a formidable team. Because of the respect that Earl had for Janet and the respect that Earl had for women in the firm in the general, I know that I always took for granted the fact that women would have the same opportunities as men because that was my personal experience. When I started to hear what was going from friends at other firms, even during our articling year, it was a bit of a surprise to me. I now think that I and my colleagues at Lerners have been somewhat sheltered. We achieved gender parity within our partnership a few years ago; it does fluctuate, but I am pretty happy with that. I do think that where we need to turn our focus now is on some of the other areas of diversity and inclusion, including on retaining and promoting racialized lawyers and staff members. I am happy with where we are in the junior lawyer ranks, which says to me that maybe we are doing well on the recruitment side. But the question is, can we retain a diverse group lawyers through to equity partnership? What could we be doing differently to achieve that objective? I know that there are a lot of firms looking at their recruitment and promotion processes. We are doing the same. But among our junior lawyers in particular, I am pretty happy with where we are. What we have to do is make sure they stay fulfilled and challenged, and that they see opportunities for advancement. That is our next challenge as a firm. 2. WHAT STEPS (OR INITIATIVES) HAS YOUR FIRM TAKEN TO ADDRESS AND IMPROVE EDI? When I started the Diversity and Inclusion Committee in September, 2017, I had never been on a committee like this. I said that I would Chair it. I don’t think I appreciated what a big bite I was taking. We started with my vision, because when you start something like that, you have to do some planning initially and then float the plan out there and see if you get traction. Luckily, I did and we had many enthusiastic contributors within a short period of time. Initially, I sent a firm wide email, advising that I was starting the Committee, and asked: “Who wants to be involved?” There is always early trepidation because people are not sure what the time commitment will be, what it involves, etc. But I had an intrepid group of about eight people who agreed to work with me on this journey. I was really pleased that we had broad representation within the firm, among both lawyers and staff members. I brought an initial outline of a plan to the group and then we worked together to generate ideas, plan monthly initiatives, and carry them forward. It was exciting to see that we had many more ideas than we could use in a single year. I have since talked to people at other firms where the work of the committee is really a management-led process. That may very well be necessary in firms larger than ours, but we were able to get participation and leadership from everyone on the Committee. We sit around a table with legal assistants, law clerks, partners, our administrative team, human resources, and marketing discussing, “What do you think we should do?” Everybody was an equal contributor and I saw people taking on leadership opportunities that had not previously existed. The Committee has generated so much enthusiasm that when I solicited interest a few months ago for people to sit on the Committee in 2019, I received over 30 positive responses. I was a bit overwhelmed by that; a 30-person committee can be unwieldy, but when I considered our inclusion mandate I knew I couldn’t say no to anybody. I am now in the process of trying to create something in which everybody feels engaged and interested. While that will be a challenge, the message I got was that people see value in the work of the Committee and wanted to be a part of it. We decided in our first year that our theme was going to be very modest: “making Lerners a better place to work”. We always thought that Lerners was a good place to work, but there are always ways to improve. Every initiative that we took was in furtherance of that objective. We came up with various monthly initiatives through internal focus groups without looking at what other firms were doing. Nothing we did was revolutionary, but we created what we thought would work for us. We had, for example, an anti-harassment training session that was mandatory for everyone at the firm and received very positive feedback about it. I think most people expected the training to focus on sexual harassment and discrimination in the workplace. We wanted our training to be broader than that – it also dealt with how to deal with differences that come up in the workplace, the more subtle things like treating everyone in the firm with respect and looking at things from the perspective of someone who might come from a different cultural or ethnic background. We had “case studies” that presented challenging sets of facts that we discussed as a group. The idea of engendering a culture of respect also became our theme for a strategic planning process that we undertook at the same time. Respect is one of our firm core values and we rolled out the strategic plan on the basis that it was critical to achieving success. That idea really arose out of our diversity and inclusion initiatives. Like many firms, we also organized unconscious bias training for all members of the firm. We were looked at the issue primarily from the perspective of our recruitment process and it has changed the way we talk about recruiting now. We used to hear people saying things like, “I really think this candidate would fit in well in the group”. And now because of the unconscious bias training, we are saying to ourselves and to each other, “Am I supporting recruitment of somebody because they are like me?” We also created a Lerners Diversity Award, which was given out at our end-of-year party. I sent an email to everyone in the firm, asking for nominations of those who advanced the objectives of equality, diversity, and inclusion at Lerners in 2018. I received lots of responses and, interestingly enough, there were very clear winners. One person in each office stood out to our colleagues among everybody who did a lot of work. Other initiatives that we undertook last year included working with a community charity group on International Women’s Day. Members of the firm were asked to bring in clothes suitable for work to support an organization that donates clothes to women who are looking for a jobs. We had a great response. We also had a speaker come in and talk about Indigenous law and we had a great turnout for that. I was blessed with having a committee whose members were very enthusiastic and rolled up their sleeves and were willing to put in a lot of time and effort to make these initiatives successful. 3. WHICH INITIATIVE HAS BEEN THE MOST SUCCESSFUL? AND WHY? Interesting enough, our most successful event last year was the one that was the easiest one to organize and the least costly: it was a potluck. Last summer we had a “Celebrating Our Diversity Through Food” potluck. Anybody who wanted to participate contributed food for a buffet lunch. We had all contributions set up in a board room. The contributors put up little signs describing the food they had made and brought. The event really brought people together and overwhelmingly I heard from members of the firm that it was their favourite event. We learned that when you get creative, you can make a lot of headway without spending a lot of money. 4. WHICH INITIATIVE WAS THE LEAST SUCCESSFUL (WHAT’S NOT WORKING)? AND WHY? The initiatives I found to be less successful were those in which we brought in speakers. And that is not because our speakers weren’t good; they were excellent. But people really enjoyed the months in which the initiative involved interaction and engagement with each other. People preferred the sessions in which we would have a case study or a problem to talk about, as opposed to having somebody come in and talk. I was surprised by that because we as lawyers tend to think that having a lecture is a great way to learn something. But really if your objective is to bring people together, having something interactive makes the most sense. 5. WHAT DO YOU HOPE TO ACHIEVE THROUGH YOUR EDI-FOCUSED ACTIONS? AND HOW DO YOU MEASURE PROGRESS? I struggle with how to measure our progress. I know that in 2019, the Law Society of Ontario will be requiring firms to provide statistical data, which will be published and will allow firms some way to measure progress. I think that will be useful. And I do think we have to measure success. But I feel like a lot of what we are doing that works is more intangible than that because it is helping to create a sense of belonging. I want to really carry forward the idea of respect in the workplace into 2019. If I hear that something has gone on or a conversation that has taken place that shouldn’t have, my role as managing partner is to address that. And I think every partner and every lawyer needs to set an example. Right now, I am measuring success by the fact that I am finding people getting together and enjoying one another’s company and contributing. I see clear leaders emerging from among the staff and more junior lawyers. Some volunteers on the Committee told me that they had never volunteered for a single firm committee before. Also because of our Committee and I our initiatives, I know more of our staff members. So those things are my way to measure success at the moment. Long term, that won’t be good enough. But right now, I am taking these little victories as they come. --------------------------------------------------- Thank you Lisa for this interview and for participating in this series. Sign up to have these profiles sent directly to your email address and stay tuned for the next post soon! The Women Leading in Law series will also return. Keep sending in suggestions for amazing women lawyers to be profiled.  “How can such a feminist, not be a feminist?” This thought popped into my head more than once as I voraciously consumed Constance Backhouse’s biography of former Supreme Court of Canada Justice Claire L’Heureux-Dubé called “Claire L’Heureux-Dubé: A Life”. The book truly covers all of L’Heureux-Dubé's life, from her pre-birth family history to her post-retirement activities, including her complicated relationship with her father, the important role her mother played in her life, how she became known as the “Great Dissenter”, and the personal tragedies that befell her. Backhouse bookends the 545 paged biography (excluding 200 pages of endnotes) with L’Heureux-Dubé's reasons in the R. v. Ewanchuk decision and the public fallout and harsh personal criticism she endured as a result. What stood out for me though, throughout reading this book, was a repeated refrain that L’Heureux-Dubé did not identify as a feminist. Professor Backhouse notes that L’Heureux-Dubé “was not someone who would ever claim membership in ‘women’s lib’” (p.228) and that “[t]he irony was that Claire L’Heureux-Dube rose to become a flag bearer for a movement to which she never belonged.”(p.229) One excerpt is particularly revealing. When a group of women “invaded” a Quebec tavern that barred women (but made an exception for L’Heureux-Dubé when she lunched there with her colleagues when she was a practicing lawyer) and started “crying out loud that they had a right to sit in a tavern just as men did”, L’Heureux-Dubé observed: They called themselves feminists in a place where men were drinking their pay while their wives were crying in our offices unable to pay their debts. To me, they were a bunch of crazy women, while we were fighting for justice where justice counted, in courts and before the legislature. The word feminist for me from thereon was associated with those crazy women and I never wanted to be part of it. (p.206) This passage I think explains a lot. And I understand. While I have always identified with feminist ideals and causes, I have not always called myself a “feminist”. In my third year of undergrad, I enrolled in a feminist literary criticism course. One day when I was leaving the seminar room a fellow student started a conversation with me, saying: “I’m not sure if I like the word ‘feminist’ to be honest, I’m not sure if I would call myself that, perhaps there is a better word?” At the beginning of the next class another student stood up to explain to the whole class how she overheard “some students” (looking at me and my walking companion) say that they did not identify as feminists. She “could not believe that women in the year 2000 (!) thought this way” and she suggested that we had no place in that classroom or words to that effect. I felt embarrassed, I felt ashamed, I felt enraged, but most importantly I thought – if THIS is what it means to be a feminist and what feminism stood for, I want no part of it. I started calling myself an “equalist” for the next few years before I came to my senses and embraced being a feminist again. The point of this story though is I never stopped acting like a feminist or advocating on behalf of women’s rights, I simply stopped labelling myself a feminist. The label didn’t fit. It just didn’t feel right to me. And while I am comfortable with and fully embrace this label now, I do not judge other women or men who do not call themselves feminists. Do they support gender equality? Do they advocate for women’s rights? That’s all I care about. It was the critics (and supporters) that labelled L’Heureux-Dubé a feminist and because of this she built a reputation as one. However, what is clear from this book is that it is not a label that fits or feels right to her. This does not diminish her advances in the fight for women’s equality or her steps in paving the way for other women to gain access to the bench. Another observation: In commenting on her appointment to the bench and promotion up the judicial ladder, L’Heureux-Dubé and other female judges featured in the book often commented that they were “just in the right place at the right time”. I always bristle a little bit when distinguished, competent, and intelligent women say this. And I hear it a lot. I attended a session by the OBA’s Women Lawyers Forum called “Pathways to Power: Getting More Women on the Bench”. Every woman judge on the panel stated this as well, that she “was just in the right place at the right time”. While I know this is likely an act of humility and no harm is meant, I believe such a comment can do a disservice to women seeking out judicial positions and may discourage women from applying to the bench at all. This makes it sound like a judicial appointment is all luck or serendipity. It could discourage women from readying themselves appropriately (taking the steps to build a career and legal experience that would attract a judicial appointment) and downplays the significant work that these women accomplished before being appointed. Yes, luck or serendipity may play a role, but I do not believe it is simply a case of “being in the right place, at the right time”. While Backhouse also concludes that L’Heureux-Dubé was in “the right place at the right time”, she suggests that the feminist movement deserves some credit too. L’Heureux-Dubé: “was unattached to the burgeoning new feminist organizations. But when the politicians went looking, she was in the right place at the right time. Simply by being the most senior woman in private practice in Quebec, she was the obvious woman for the job. . . Her opportunity emerged because the women’s movement insisted on change.”(pp.228-229) Overall, this was a book I could not put down once I started and finished it in under a week. I would be working at my office and I would count down the hours until I could go home and pick it up again. Perhaps it is just the legal geek in me who loves anything to do with law, but I believe it had more to do with the excellent story telling on the part of Backhouse. She drew you in to the life of L’Heureux-Dubé , but left her own impression on you, the reader, as well. Backhouse’s views were provided, but in a subtle way. She was always there guiding the reader and reminding her of a different interpretation as to the events that occurred, an outside observer’s perspective on very personal inside accounts. Aside from the fascinating feminist analysis Backhouse brings to L’Heureux-Dubé’s life and career, this book offers so much more to lawyers, law students, or anyone interested in Canadian legal history. Last week the Sunday Edition of CBC Radio One aired a documentary that put a spotlight on an important topic in the legal profession: mental health awareness and the need to end the stigma against mental illness. The documentary was about the real reason former Supreme Court of Canada Justice Gerald Le Dain left the bench. He was asked to resign after suffering from depression and denied a chance to take a leave. My blog post about the documentary and a link to it can be found here.

According to the producer, Bonnie Brown, after the documentary aired the CBC received a great deal of feedback in letters and comments on social media, including inquiries on the prospects of a formal apology, what happened to Justice Le Dain after he resigned, and why he was not given credit for significant judgments to which he had contributed. As a result, the CBC will be doing follow-up coverage this weekend, where host Gillian Findlay and Bonnie Brown will read some of the mail and along with David Butt (who clerked with Justice Le Dain) discuss the epilogue to the documentary. The answer to "What happened next?" is not a happy one. The follow-up coverage will air in hour two of the show on Sunday between 10:10 am and 11:00 am and will be posted online tonight around 6pm Eastern. [UPDATE: Documentary now available online here.]

Lawyers should tune into The Sunday Edition on CBC Radio this weekend to listen to a documentary that Talin Vartanian , a produce of the Sunday Edition, stated will “reveal what happened to one of the greatest legal minds of the country.” The documentary is called “One Judge Down” and is about former Supreme Court of Canada Justice Gerald Le Dain. Justice Le Dain is best known in the public for the 1973 Le Dain Commission of Inquiry into the Non-Medical Use of Drugs, which was far ahead of its time in recommending the decriminalization of marijuana. But, it is what the public doesn’t know about Justice Le Dain's legal career that is far more interesting and unfortunately distressing. CBC’s synopsis of the documentary: After serving for 9 years on the Federal Court of Appeal, Le Dain was nominated to the Supreme Court of Canada by Trudeau (Sr.) in 1984, where he served for just four years. Then, at age 63, he decided to resign...abruptly. At least, that's what people thought. In fact, the Chief Justice at the time, Brian Dickson, demanded Le Dain's resignation. It happened after Le Dain's wife, Cynthia, asked Dickson for some time off for her husband. He'd been struggling with his caseload, and had fallen into a depression. But instead of granting a leave, Dickson decided that Le Dain's days on the bench were over. Many of those who knew about it at the time -- judges, lawyers, law professors and family members -- have kept quiet for almost thirty years. And many are highly critical of the way the Chief Justice treated Gerald Le Dain. In our documentary, those closest to Le Dain are now speaking out on his behalf. They include Claire L'Heureux-Dubé, the last surviving Supreme Court justice from Le Dain's era; Harry Arthurs, former President of York University; Justice Melvyn Green of the Ontario Court of Justice; David Butt, now a top criminal lawyer in Toronto who served as a Supreme Court clerk; McGill law prof Richard Janda, also a court clerk under Le Dain; and Caroline Burgess, one of Gerald Le Dain's daughters. The producer of this story is Bonnie Brown, who has been an award-winning documentary and news producer for the CBC for about twenty years. She also has a law degree from McGill. This should make for an interesting listen and will hopefully address an important subject: mental health and wellness in the legal profession. While some strides have been made in recent years, there is still a need to confront the mental health stigma that exists. "One Judge Down" will be published on CBC’s web site on the evening of January 12th and will air on The Sunday Edition January 14th. ADDENDUM On February 27, 2018 I attended a presentation by Justice Robert Sharpe discussing the life of Chief Justice Brian Dickson (Justice Sharpe, along with Kent Roach wrote a book about Dickson called "Brian Dickson: A Judge's Journey") at a program hosted by the Osgoode Society of Canadian Legal History. During question period, after a 40 minute talk by Justice Sharpe, a member of the audience asked Justice Sharpe about the documentary "One Judge Down" noting that he thought perhaps the documentary was a bit one-sided and if Justice Sharpe had any comments to make regarding Dickson's actions. Justice Sharpe stated that he had been contacted by the producer, Bonnie Brown, but that instead of participating in the documentary he referred her to his account of the resignation of Justice Le Dain in his book. He stood by what was in his book. Justice Sharpe was clear that it was just a sad, horrible situation, and that Dickson followed the law and did what he had to do. He explained that after Le Dain was "severely disabled" for three months, Le Dain would have been asked to resign as the Supreme Court just could not function with less than nine judges for a long period of time, according to the law (Justice Sharpe did not refer to which law). Dickson, however, went to the Minister of Justice and asked for an extension for Le Dain for another month. Then when Le Dain still could not sit as a judge, Dickson went back to the Minister of Justice for another extension. It was at this point that Le Dain resign. Following this explanation, the next question came from Bonnie Brown herself who was in the audience (unbeknownst to I assume everyone, but clearly to Justice Sharpe). Bonnie questioned Justice Sharpe's account saying that his reference to the months and the extension request etc. were not in his book and that she would have liked to have heard about this for the documentary. She also questioned Justice Sharpe's dates and timing as the three months, plus one month, plus one month, did not match with the recollections of the Le Dain family. Justice Sharpe replied that this information was in his book and that not everyone is remembering it the same way and may not be recalling the time correctly. Question period was then over. As both of the key players are no longer alive and able to give their versions of the events, perhaps we will never truly know what occurred. All I know is that this story has brought a lot of attention to the struggles of mental illness and how it affects the legal profession. The take away from all of this is that we can all do a little bit better, and if we do not have the tools in place, or are unaware of how to help others with their illness, we can and must educate ourselves. While it is easy to focus on what is wrong with the legal profession (including gender inequality, lack of diversity and inclusion, etc.) not everything is as bleak as it seems sometimes.

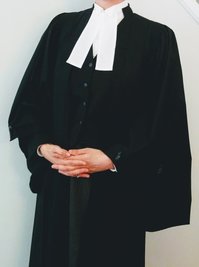

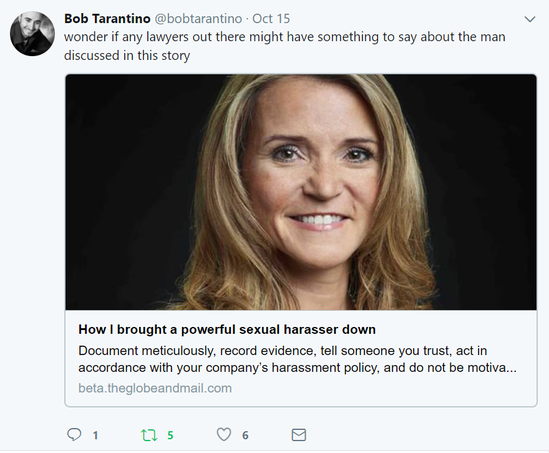

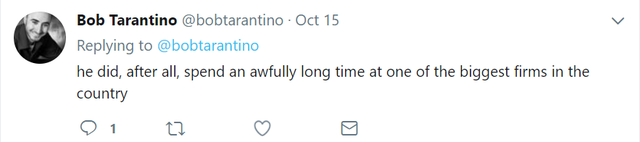

Starting in January 2018 I will be focusing on some of the "good" by profiling amazing women lawyers doing some amazing things in law. Each post in my series "Women Leading in Law" will include an interview with a lawyer, highlighting her practice or legal business, and her tips for women starting out in law. Stay tuned. . . .  There is no shortage of articles, papers, blog posts, and even hashtags, asking the question “Why are women leaving law?” We need to stop this. We need to stop asking why are women leaving. Instead, we need to start asking why is the legal profession forcing women out? You may see this as a distinction without a difference, but I disagree. Words matter. With the rise of sexual assault reports in the news, some have noted that we should stop talking about women being assaulted or women being harassed as this ignores the perpetrators entirely. We should be talking about men assaulting women or men harassing women. In the same vein, when asking “why are women leaving?”, we are putting the emphasis on the women’s actions, and the question ignores the actions or role that law firms or legal departments play in the gender inequality that plagues our profession. Also, by saying that women are leaving implies that they have a choice in the matter. On the surface, it may appear that these women are “choosing” to leave. But how much of it is an actual choice and how much of it involves factors completely out of their control? Women of all ages and stages are being forced out of law. It is not just women of child bearing years trying to “balance it all”. Women are being pushed out in their 40s and 50s too. We are trickling out “by a few percentage points per year of age”. We all know that women are graduating law school at equal or greater numbers than our male counterparts and have been for a number of years. Something is happening once we become lawyers. We get tired. Women get worn down, sick of having to play the game, putting up with the inequality, the discrimination . . . Slowly but surely it just becomes too much. And sometimes the reason is much more overt. I know several women who have left firms, in-house legal departments, or the law entirely, and their “official” story is that they were making a choice that they felt was right for them or their families. But when I’ve spoken to these women in private, or more likely after a glass of wine or two, the whole truth emerges. They didn’t want to leave, they were told to. Or, they were advised that it was a good idea to explore their “options”. In other words, try and find a new job, you have no future here. There was no formal termination of their employment but the proverbial “writing was on the wall”. I understand why firms or legal departments take this tactic. Management claims that it is in the best interests of the lawyer to give them the option to leave. They are giving the lawyer a better chance to find a new job, to ‘save face’, and not have to admit they were “let go”. You would have to be extremely naïve to believe that firms do this solely out of concern for the lawyer. How bad would it look if firms and legal departments were actively letting go women lawyers? I’ve had at least half a dozen women tell me this same story. I can only imagine the number out there who remain silent. No one wants that stigma attached to their legal careers. Whether subtle or overt actions are pushing women out, the numbers are clear: there is still a major issue with the retention and promotion of women in law. By asking why are women leaving, we can dismiss it as a “women’s issue”; one that women must fix. Instead, we should be explicitly acknowledging the role that law firms and legal departments play. Let’s start asking why is the legal profession forcing women out? And when is it going to stop? A lot has been written about the sexual predator Harvey Weinstein this past week and has prompted much discussion about men sexually harassing and assaulting women. As we all know this behaviour is not limited to the Hollywood elite, but invades the lives of all women. The Canadian legal landscape is not immune. We have our Weinsteins too. As Professor Amy Salyzyn wrote “women know who the predators are”. We whisper their names among ourselves. We tell stories of “remember that time when . . .” and often try to laugh it off. Nevertheless, when the #MeToo campaign began on Twitter and Facebook, my first thought was “Well, I’ve been relatively lucky, should I write #MeToo?” But I let my mind process that for a bit. And then I remembered “that incident” and “the other incident” and the “oh my goodness, how could I forget THAT time”. We learn to grin and bear it, try to forget it, and move on. We are taught not to make waves and a career self-preservation mode kicks in: “If I complain will I be punished?" "Will other male lawyers not want to work with me?” “Will I become known as the trouble maker and not make partner?” This is often followed by an immense sense of guilt for not saying anything. This weekend Leanne Nicolle wrote an opinion piece for the Globe and Mail talking about her 2015 complaint against the president of the Canadian Olympic Committee. In 2015 the president of the COC was Marcel Aubut, who is also a lawyer who worked for several years at Heenan Blaikie. As lawyer Bob Tarantino noted on Twitter: I read about Mr. Aubut in the book Breakdown: The Inside Story of the Rise and Fall of Heenan Blaikie.[1] The author, Norman Bacal, noted that the “road was littered with bodies of those whom Marcel had steamrolled after he decided they stood in the way of his dreams or objectives”. While there is a whole chapter devoted to the powerful Mr. Aubut, the following paragraph by Mr. Bacal (who had been the co-managing partner of Heenan for several years) stands out:

“[Marcel] understood at a cerebral level that a man in his position should not be taking the slightest risk with female support staff or associates, especially since he knew a misconstrued comment or touch could taint a successful career. I could not begin to speculate on how his behaviour may have been perceived by those who worked for him when he was president of the Canadian Olympic Committee. His resignation from that position in 2015 may have been construed by some as a day of reckoning, but for those of us who knew the man well, it was simply a very sad day.” Mr. Bacal’s response is just as telling as the allegations against Mr. Aubut. The concern here being the affect a complaint could have on Mr. Aubut’s career (not how his behaviour would affect the female support staff or associates) or how his behaviour could be “misconstrued”. I can’t tell you the number of times that sexual harassment I have witnessed has been labelled as “misconstrued”, taking the blame from the harasser and laying it squarely on the harassed: “You’re too sensitive, can’t you take a joke?” or “Oh, he was raised in a different time; it’s just an innocent comment”. Note that over 100 people came forward to share their experiences with Mr. Aubut in the formal review. The findings of the review concluded that a majority of COC staff interviewed reported "experiencing or witnessing harassment (both sexual and personal) during the President's tenure, both inside and outside of the COC's offices". Oh, but I'm sure these actions were just "misconstrued". Ethics professors Alice Woolley and Adam Dodek have written thoughtful and insightful articles on the issue of sexual harassment in the legal profession and the potential for abuse of articling students. Professor Salyzyn noted that Professor Woolley’s article was “written roughly three years ago and we have not yet, as a profession, full-throatedly taken up Professor Woolley’s call to begin the conversation and progress towards the type of change we need. I’m optimistic that we will eventually reach a tipping point. But, whether we’ll have the moral leadership and courage to reach this point ourselves or, alternatively, have it externally thrust on us, as have other industries, remains to be seen.” When I’ve talked to people about the systemic discrimination of women in the legal profession I’ve often naively said, “Well, at least we aren’t being slapped on the butt and called ‘toots’ anymore”. . . I don’t think I will be saying that again. [1] Bacal, Norman. Breakdown: The Rise and Fall of Heenan Blaikie. Toronto: Barlow Books, 2017. See my feminist review of this book here.  A few weeks ago I attended a program sponsored by the Ontario Bar Association’s Constitutional, Civil Liberties and Human Rights Law section called “Lawyers as Agents for Change: Tackling Hate, Racism, Xenophobia from a Practitioner’s Perspective”. The program’s goal was to have its expert panel unravel key questions from a lawyer’s perspective on how to fight hate and racism, both when our clients are faced with these issues, and when they invade our daily legal practices. The panel consisted of Anita Bromberg (the Director of Advocacy and Engagement, Friends of Simon Wiesenthal Center), Mihad Fahmy (Barrister & Solicitor and Chair, Human Rights Committee, National Council of Canadian Muslims) and Corey Shefman (Olthuis Kleer Townshend LLP). The discussion was moderated by lawyer Richa Sandill (MacDonald & Associates). A few discussion points are summarized below: Rising Tide of Hate or Willful Blindness? The first question addressed was whether there really was a “rising tide of hate” in Canada or whether racism and hate that has always been here has just bubbled to the surface, and now has a spotlight on it? Ms. Bromberg wanted to be “very clear and careful that we don’t blame others for situations we have here in Canada,” alluding to the Trump administration and other racially motivated hate crimes in the United States. For example she referred to an anti-Semitic sign that was painted on an overpass on Highway 400: “That’s not Trump egging this person on. Our first step is to take responsibility that Canada has its hate.” Ms. Bromberg also admitted though that there has been a measurable rise in hate activity, but took the position that someone has pulled back the curtain and emboldened those that have always been here. “Our job as lawyers is to get at the underlying cause,” said Ms. Bromberg. Corey Shefman agreed that racism has always been here in Canada and we cannot blame the events from south of the border: “Some things have never been hidden; it depends on who you are.” Mr. Shefman gave the example of whenever any article involving Indigenous persons is posted on a major Canadian media website the comment section is always shut off due to the toxic nature of the comments. Ms. Fahmy observed that her own experiences have been different than her children’s. Growing up, Muslims in Canada were in such small numbers that others were simply curious about them. Now, “Muslims don’t feel safe”, she said. As their numbers grew and they entered institutions, the fear grew. As lawyers it is our job to help in the process to make them feel safe and included and that sometimes “we don’t have the luxury to try to figure out the root causes”. Legal Remedies for our Clients Mr. Shefman noted that the repeal of section 13 of the Canadian Human Rights Act (this section prohibited speech inciting hatred of people based on race, religion, sexual orientation and other protected characteristics) was unfortunate, and the lawyer’s toolbox has shrunk. “We have to become more creative,” he observed. As an example, during an inquest in Winnipeg where the deceased was an Indigenous victim of a police shooting Mr. Shefman argued that the inquest should consider whether systemic racism played a role in his death. A motion was required to have this issue even considered (not to make a finding that systemic racism played a role, but just to have it considered in the first place). The panelists also note that while the Criminal Code and criminal proceedings represent one legal remedy, the Criminal Code can be a blunt instrument, and you need third party involvement in laying charges. The Criminal Code can be softened with restorative sentences, noted Ms. Bromberg. The overall consensus from the panel was that as lawyers, acting on behalf of our clients, we need to look outside the box for legal remedies. There is little common law on racism and hate and the available legislation is not as helpful. Ms. Bromberg encouraged us as lawyers to discuss among ourselves what tools we want added to our toolbox. Lawyers are privileged, and as advocates we can ask the Attorney General to stop sitting on hate crimes and put pressure on the Attorney General and the government for change. Non-Legal Involvement Ms. Fahmy advised lawyers to look at “what can we do in our non-legal sphere as human rights advocates”, citing as an example the large number of individuals who turned out to protest an anti-Muslim rally that was planned in London, Ontario. “Sometimes we have to take our lawyer hats off and see what the institutions call for,” said Ms. Fahmy, “Police units need a lot more funding; we can reach out to communities, etc.” Mr. Shefman agreed that the skills we have as lawyers translate to non-legal advocacy as well. We also need to build coalitions and networks and ask how can our institutions (the OBA, LSUC, CBA) use their powerful voices? Day-to-Day Agents of Change Lawyers can also bring about change in our day to day practice and interactions with other lawyers. Ms. Fahmy suggested mentoring racialized lawyers and to not wait for them to bring up these issues: “It is up to us to open the conversation”. She also said that “most often it is subtle and not obvious hate comments. Am I being bullied because the opposing lawyer is a bully? Or is it because I am a new lawyer? Or is it because I am a woman of colour and in a hijab? It’s hard to know. All you can do is do your job and do it well. How do you deal with subtle comments? Do a good job for your client.” “Sometimes you have to throw tact out the window”, said Ms. Bromberg when dealing with hateful or racist comments in practice. Mr. Shefman’s advice to a young lawyer wanting to be an agent for change is to “pick an issue”. As lawyers we can over-extend ourselves. Keep your eyes open for opportunities and volunteer. Also, as lawyers we are in a privileged position but “don’t assume that when you walk into an organization that you will be in charge. There is great value to standing at the back of the room and listening.” Lawyers need to spend more time on the street, in the classroom, and in the community. Conclusion Overall it was a helpful starting point in discussing how lawyers can become or continue to be agents for change. I believe it is our professional duty to take up these roles and advocate on behalf of those who may not be in such privileged positions. I look forward to future programs from the OBA, CBA, LSUC and other organizations on this topic.  As a civil litigator in Ontario, when I appear before a judge (in most circumstances) I must wear my court attire consisting of black or grey "court striped" pants or skirt, a white wingtip collared shirt, waistcoat, my robe and my tabs (white flappy things that flow from my collar – see picture). If you are interested, there have been several articles written about the history of our stuffy courtroom attire and how to properly wear it, gussy-it-up, and about the makers who make them. Some litigators loath the robes, wishing to do away with the old-fashioned garb and the blue velvet carrying bags with our initials on them (see photo below); others feel at home in the serious and traditional uniform. What I appreciate the most about my robe is that, as a woman, I feel like it helps level the playing field for me in the courtroom. Women are often judged on how we look and are dressed, and women lawyers in the courtroom are no exception. Judges judge us by appearance whether consciously or unconsciously - they are human. The robes act as a great equalizer. We all look equally ridiculous in them, whether we are hiding breasts or a pot belly underneath. When I am wearing the same Hogwarts outfit as counsel next to me, I know the judge is not judging me on my choice of dress. If I had my way I would bring back the wigs and then I wouldn’t have to worry about my hair either (Up? Down? Bun? Pony tail? Curly? Straight? Pig tails (probably not)). Unfortunately, we don’t robe before Masters (yes, we have individuals called “Masters” in our court system). When I appear before a Master I waste so much time thinking about my attire: should I stick to a boring black suit? Skirt or pants? Skirt too short? What colour of top? Too bright? Too dowdy? Too low cut? Not serious enough? Too serious? And don't get me started about my shoe choice! And I admit, I tend to be an over-thinker, but if how I dress can potentially affect the outcome for my client, then of course I am going to put thought into it. Men have it so easy: suit, shirt and tie. I totally prefer wearing my robe. I know change is coming to the legal profession (including potentially renaming the Law Society of Upper Canada) and I welcome change, but I hope some traditions remain, including our wacky courtroom attire. |

Erin C. Cowling is a former freelance lawyer, entrepreneur, business and career consultant, speaker, writer and CEO and Founder of Flex Legal Network Inc., a network of freelance lawyers.

Categories

All

Archives

December 2022

|

|

(C) 2014-2024 Cowling Legal. All rights reserved.

|

Please note I am not currently practicing law.

Information on this website does not constitute legal advice and is for informational purposes only. Accessing or using this website does not create a solicitor-client relationship. See website Terms of Use/Privacy Policy. info@cowlinglegal.com

3080 Yonge Street, Suite 6060 Toronto,ON M4N 3N1 (appointment only) |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed